Albert Leslie Singleton was born in 1887, the youngest of the six children of Thomas and Margaret Singleton. The family owned and ran a store and butchery at Lower Lewis Ponds from 1872 until 1920. Because it was a substantial brick structure, the building still survives, but is now called Wildwood Cottage. The rest of the old 19th century village of Lower Lewis Ponds has disappeared.

Despite his father having been a board member of the local school at Ophir, Albert was educated in Sydney at Stanmore and Petersham Public Schools. Probably Albert boarded with his aunt Cecilia Brady, who lived in Newtown and Petersham during the years Albert was at school. His Brady cousins, Reg and Vic, would have gone to the same schools.

In 1907 his father died, and Albert and his older brother Arthur ran the store. The district of Lewis Ponds was in decline as people moved away from the old gold fields. Albert left in 1913 to make his own way in the world, working firstly in Murrurundi and then in Gundagai as head grocer for George F. Grill’s Railway Store. He had prior experience from the family store.

With the awful news from Gallipoli through 1915, there was a surge of volunteers enlisting in the AIF. So on 3 September 1915, Albert Singleton (4316) with his mate from Gundagai, Leo Boyton (4150), enlisted in the Army at Cootamundra. They joined the 1st Battalion, 13th Reinforcement as privates.

On 20 December 1915, (by this time they were three musketeers – Private Jack Edward Smith (4311) from Taree had joined them) Albert, Leo and Jack embarked upon HMAT Aeneas for Egypt.

In Egypt on 16 February 1916, they were allotted to and joined the 54th Battalion of the Australian 5th Division at Tel-el-Kebir near Cairo. Of the Battalion’s 1,023 soldiers, 500 were raw reinforcements like Albert, Leo and Jack. Here Albert became best friends with another young man from the Orange district, Private Charlie Campbell (3482), who had come out as a reinforcement on a different ship, but who was now also in the 54th Battalion.

The 5th Division had been assigned to take over defence of a section of the Suez Canal. Commanding officer Major General McCay decided to turn this into a training exercise and on 28 March 1916 ordered the entire Division to march the 65 kilometres through the desert to Moascar in full battle kit in 40 degree heat. Many of the soldiers suffered heat exhaustion, and in the evening, ambulance wagons and camels collected these soldiers from the desert where they had collapsed.

On 19 June 1916 the 54th Battalion embarked from Alexandria on the Caledonian, to join the British Expeditionary Forces in France, arriving at Marseilles on 29 June. They were then marched up to the front line at Fleurbaix.

Without any time to acquaint themselves with their surroundings, the Battalions of the 5th Division were assigned to attack the fortified German lines. This action is now known as the Battle of Fromelles. (Fleurbaix and Fromelles are 5km apart, the former behind the British lines and the latter behind German lines). They were assembled to attack in four waves at five minute intervals. The first wave was to take the first German trench and clear it of the enemy. Subsequent waves of attackers were to leap-frog the first trench and take second and third German support trenches that had been identified from aerial reconnaissance.

So rushed had been the planning of the attack, that there were not enough steel helmets for the third and fourth waves, who were forced to attack in their felt slouch hats.

A seven-hour long artillery bombardment of the German lines began at 11am on 19 July. The Germans, however, were aware of the troops massing in the trenches opposite, preparing to attack, and their artillery soon found their range and caused significant casualties amongst the waiting Australians.

At 5.45pm the order to attack was issued and the 54th Battalion – Albert and his mates – “hopped the bags” (went over the top).

They achieved their objectives, but found that the second and third German support trenches didn’t exist – they were shallow water-filled ditches providing them little cover from German rifles and machine guns. Nonetheless, they attempted to defend these ditches, digging into the gluey Flanders clay and filling sand bags from which to construct a parapet. Night fell at around 9pm.

At 11.45 pm the Germans launched a concerted counter-attack. It was at this time, at around midnight of 19 July or early in the morning of 20 July 1916, that Albert was killed. He was shot through the head. One can’t help but suspect he was one of those without a helmet. He was 28 years old.

As morning broke on 20 July, at 7.50am the Battalion was ordered to retreat. Albert’s body was left behind in the German lines, and was probably one of those Australian soldiers buried by the Germans in the mass graves at Fromelles. He has no known grave.

His mates Charlie Campbell and Jack Smith were wounded the same evening. The 54th Battalion had suffered 540 casualties including 155 deaths.

When Albert was killed his sister, Nurse Lilly Singleton, made enquiries about the manner of his death and where he was buried. She wrote to his mate, Private Leo Boyton, who told her what he knew.

A year later in 1917, the Australian Red Cross Wounded and Missing Enquiry Bureau began looking into Albert’s death and burial. They collected eye-witness accounts from six soldiers in the 54th who had seen his death – Lance Corporal Horace Balcomb and Privates Charles Campbell, Leo Boyton, Jack Smith, R.W. Fairweather and R.J. Eyles.

Private Charlie Campbell gives the best description of Albert: “He was of slight build and very fair, with light curly hair and bald on the top. He was about 5ft 10 inches in height and 26 or 27 years of age. He had very neat ways, rather sharp features.” One of the others stated he had brown eyes, but his enlistment papers say blue. Charlie later told his Sergeant, Sgt S. Hill, that he had lost his best friend at Fleurbaix – Albert Singleton.

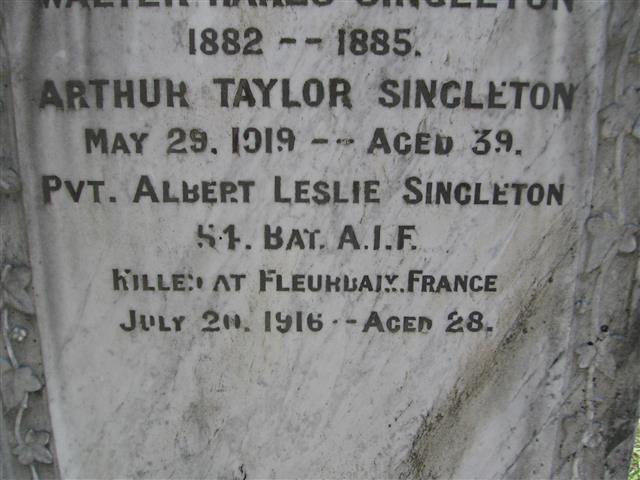

Albert Leslie Singleton is commemorated on St Joseph’s Church Orange Honour Roll, and the family headstone in Orange Cemetery. His name appears on the World War I Roll of Honour on the southern face of the Orange Cenotaph, on panel number 159 on the Roll of Honour at the Australian War Memorial in Canberra and on panel number 11, V.C. Corner of the Australian Cemetery at Fromelles in France.

In 1923 the Anzac Memorial Avenue of trees was planted along Bathurst Road in Orange, and a tree was planted in honour of Private Singleton. It was donated by Alderman William Ernest Bouffler.

In order to determine if one of the bodies recovered from the mass graves at Fromelles is that of Albert, DNA samples from the dead soldier need to be matched to samples of DNA from Albert’s relatives. Both mitochondrial and Y chromosome DNA are needed. So far genealogical research has located mitochondrial DNA from relatives in Tasmania, but no living person having the Singleton Y chromosome has been located here in Australia. Attempts are being made to trace related Singletons in the UK who might be able to help.

* Rob Cunneen, 2016